2.11.2. Projections Onto a Hyperplane¶

We can extend projections to \(\mathbb{R}^3\) and still visualize the projection as projecting a vector onto a plane. Here, the column space of matrix \(\bf{A}\) is two 3-dimension vectors, \(\bm{a}_1\) and \(\bm{a}_2\).

The span of two vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) forms a plane. As before, we have an approximation solution to \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{x} = \bm{b}\), which can be written as \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{\hat{x}} = \bm{p}\). The error is \(\bm{e} = \bm{b} - \bm{p} = \bm{b} - \mathbf{A}\,\bm{\hat{x}}\). We want to find \(\bm{\hat{x}}\) such that \(\bm{b} - \mathbf{A}\,\bm{\hat{x}}\) is orthogonal to the plane, so again we set the dot products equal to zero.

The left matrix is just \(\mathbf{A}^T\), which is size \(2{\times}3\). The size of \(\bm{\hat{x}}\) is \(2{\times}1\), so the size of \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{\hat{x}}\), like \(\bm{b}\), is \(3{\times}1\).

As with the vector projection solution of equation (2.27), equation (2.28) minimizes the error for over-determined systems of equations. The orthogonal solution makes use of QR decomposition. When \(\bf{A}\) in equation (2.28) is replaced with \(\mathbf{Q\, R}\), two matrix products reduce to the identity matrix.

Because \(\bf{A}\) is over-determined, the last \(m - n\) rows of \(\bf{R}\) will be all zeros, so we can reduce the size of \(\bf{Q}\) and \(\bf{R}\) with the economy QR option where only the first \(n\) columns of \(\bf{Q}\) are returned. \(\bf{Q}\) is now \(m{\times}n\), and \(\bf{R}\) is \(n{\times}n\). After finding \(\bf{Q}\) and \(\bf{R}\), computing the solution only requires one \(n{\times}m\) multiplication with a \(m{\times}1\) vector and then a \(n{\times}n\) back-substitution of an upper triangular matrix.

In Python, we can find \(\hat{\bm{x}}\) as:

R = scipy.linalg.cholesky(A.T @ A)

x_hat = solve_triangular(R, solve_triangular(R.T, (A.T @ b), lower=True))

# or

Q, R = scipy.linalg.qr(A, mode='economic') # Economy QR

x_hat = scipy.linalg.solve_triangular(R, (Q.T @ b))

The projection vector is then:

The projection matrix is:

Note

\(\bf{A}\) is not a square matrix and thus is not invertible. If it were, \(\mathbf{P} = \bf{I}\) and there would be no need to do the projection. Try to verify why this is the case. Recall that \((\mathbf{BA})^{-1} = \mathbf{A}^{-1}\mathbf{B}^{-1}\).

2.11.2.1. Over-determined Pseudo-inverse¶

Recall from our discussion of square matrices that while we might write the solution to \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{x} = \bm{b}\) as \(\bm{x} = \mathbf{A}^{-1} \bm{b}\), that is not how we should compute \(\bm{x}\) because computing the matrix inverse is slow. However, a one-time calculation based only on \(\bf{A}\) should be considered when we need to compute multiple solutions with a fixed \(\bf{A}\) matrix and different \(\bm{b}\)’s. We have two ways to achieve this objective that are preferred over computing the inverse of \(\bf{A}\) by elimination. One option is an LU decomposition of \(\bf{A}\) and reuse of \(\bf{L}\) and \(\bf{U}\) with a triangular solver for each \(\bm{b}\). We could also compute the inverse of \(\bf{A}\) from the SVD as shown in Singular Value Decomposition.

Similarly, we sometimes need a one-time calculation on rectangular systems that we can reuse. This is the Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse of \(\bf{A}\), which we denote as \(\bf{A}^+\), and \(\bm{x} = \mathbf{A}^+ \bm{b}\) is the least squares (minimum length) solution to \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{x} = \bm{b}\).

We have already found from projections that equation (2.30) is the least squares solution, but it has unacceptable computational performance.

Computing \(\mathbf{A}^{T}\mathbf{A}\) is slow if \(\bf{A}\) is large and the multiplication degrades the condition of the system. Although a solution using the Cholesky solver is reasonable if \(\bf{A}\) is not too large, strategies based on orthogonal matrix factorizations are preferred.

Several matrix multiplications simplify to the identity matrix if we let \(\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{Q\, R}\) or \(\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{U\,\Sigma\,V}^T\) in equation (2.30).

The solutions using the QR and SVD factors in equation (2.31) are

equivalent since computing the pseudo-inverse of \(\bf{R}\) results

in an SVD calculation. By Orthogonally Equivalent Matrices in

Golub–Kahan 1965, matrices \(\bf{A}\) and \(\bf{R}\) are

orthogonally equivalent. So if

\(\mathbf{R}^+ = \mathbf{V\,\Sigma}^+\,\mathbf{U}_r^T\), then

\(\mathbf{A}^+ = \mathbf{V\,\Sigma}^+\,\left(\mathbf{U}_r^T \mathbf{Q}^T\right)\)

is an equivalent equation to \(\mathbf{A}^+\) from the SVD of

\(\bf{A}\) in equation (2.31).

Numerical software uses the SVD to calculate the pseudo-inverses of both

over-determined system and under-determined systems The Preferred Under-determined Solution).

The pseudo-inverse is computed in Python with the command

pinvA = scipy.linalg.pinv(A).

Since \(\bf{\Sigma}\) is a diagonal matrix, its inverse is the reciprocal of the nonzero elements on the diagonal. Refer to equation (4.4) in Properties of Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors. The zero elements remain zero.

In [2]: import numpy as np

In [3]: from scipy.linalg import pinv

In [4]: S = np.diag([2, 3, 0]); print(S)

[[2 0 0]

[0 3 0]

[0 0 0]]

In [5]: print(pinv(S))

[[0.5 0. 0. ]

[0. 0.33333333 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. ]]

Here is an example of using the pseudo-inverse on an over-determined

matrix equation. Note that the full SVD calculation is not needed here.

The economy SVD (full_matrices = False option) is sufficient

(see Economy SVD).

In [6]: from scipy.linalg import pinv, svd

In [7]: A = np.random.randint(-15, 20, (4, 4))

In [8]: A = A.astype(float)

In [9]: y = np.random.randint(-10, 10, (4, 1))

In [10]: b = A @ y

In [11]: U, s, Vt = svd(A, full_matrices=False)

In [12]: pinvA = Vt.T @ pinv(np.diag(s)) @ U.T

In [13]: x = pinvA @ b

In [14]: np.allclose(x, y)

Out[14]: True

2.11.2.2. Projection Example¶

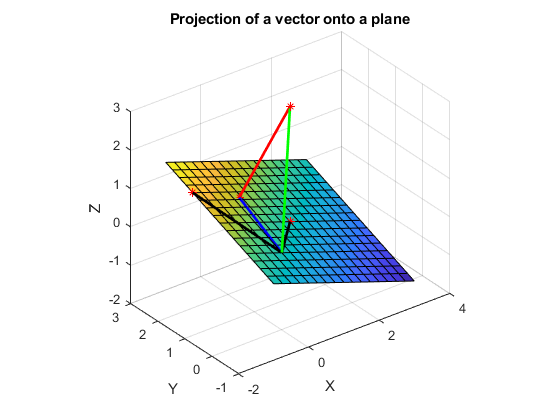

The projectR3 script and the resulting plot in figure

Fig. 2.24 demonstrate the calculation and display

of a vector’s projection onto the matrix’s column space. The dot product

is also calculated to verify orthogonality.

Fig. 2.24 The projection of a vector onto the column space of \(\bf{A}\), which spans a plane in \(\mathbb{R}^3\)¶

# File: projectR3.py

# Projection of the vector B onto the column space of A. Note that with

# three sample points, we can visualize the projection in R^3.

import numpy as np

from scipy.linalg import qr, solve_triangular

a1 = np.array([[1, 1, 0]]).T

a2 = np.array([[-1, 2, 1]]).T

A = np.hstack((a1,a2))

b = np.array([[1, 1, 3]]).T

Q, R = qr(A, mode='economic') # Economy QR

x_hat = solve_triangular(R, (Q.T @ b))

p = A @ x_hat

e = b - p

print(f'Error is orthogonal to the plane if close to zero: {p.T @ e}')

2.11.2.3. Alternate Projection Equation¶

There is another procedure for projecting a vector onto a vector space. The approach that we have used might be described as projecting a vector onto the column space of a matrix. An alternate approach projects a vector onto an equivalent vector space spanned by an orthonormal set of basis vectors. So the first step in the alternate approach is to find the orthonormal basis vectors of the matrix columns. (See Vector Spaces for help with some of the terminology.)

Let \(\mathbf{U} = \{ \bm{u}_1, \bm{u}_2, \ldots , \bm{u}_n \}\) be an orthonormal basis for the column space of matrix \(\bf{A}\). Then the projection of vector \(\bm{b}\) onto \(\text{Col}( \mathbf{A} )\) is defined by

There is a trade-off between the two algorithms. The alternative

approach finds the orthonormal basis vectors to the columns of

\(\bf{A}\) using either the Gram–Schmidt process

(Finding Orthogonal Basis Vectors), QR factorization (QR Decomposition), or the economy SVD

method (Projection and the Economy SVD), which is used by the orth function.

Whereas, projecting onto the column space requires solving an

\(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{x} = \bm{b}\) problem.

The geometry of the alternate algorithm provides a simple way to see that it also projects a vector onto a vector space.

Any vector in the vector space must be a linear combination of the orthonormal basis vectors.

The \(\bm{b}^T \bm{u}_i\) coefficients in the sum are scalars from the dot products of \(\bm{b}\) and each basis vector. Since the basis vectors are of unit length, each term in the sum is \(\left(\norm{\bm{b}}\,\cos(\theta_i)\right)\,\bm{u}_i\), where \(\theta_i\) is the angle between \(\bm{b}\) and the basis vector. Thus, each term in the sum is the projection of \(\bm{b}\) onto a basis vector.

The example in altProject script finds the projection using the two

methods.

# File: alt_project.py

# Comparison of two alternate projection equations

# Define the column space of A, which forms a plane in R^3.

import numpy as np

from scipy.linalg import qr, cholesky, solve_triangular

a1 = np.array([[1, 1 ,0]]).T

a2 = np.array([[-1, 2, 1]]).T

A = np.hstack((a1, a2))

b = np.array([[1, 1, 3]]).T

# Projection onto the column space of matrix A.

R = cholesky(A.T @ A)

x_hat = solve_triangular(R, solve_triangular(R.T, (A.T @ b), lower=True))

p = A @ x_hat

print('Projection onto column space: ')

print(p)

# Alternate projection

# The projection is the vector sum of projections onto the orthonormal

# basis vectors of the column space of A. Note the use of both

# inner product multiplication (``@``) and scalar to vector

# multiplication (``*``).

U,_ = qr(A, mode='economic')

u1 = U[:,[0]]

u2 = U[:,[1]]

p_alt = b.T @ u1 * u1 + b.T @ u2 * u2

print('Projection onto basis vectors: ')

print(p_alt)

The output from the vector projection example follows.

Projection onto column space:

[[0.18181818]

[1.81818182]

[0.54545455]]

Projection onto basis vectors:

[[0.18181818]

[1.81818182]

[0.54545455]]

2.11.2.4. Higher Dimension Projection¶

If the matrix \(\bf{A}\) is larger than \(3{\times}2\), then we can not visually plot a projection as we did above. However, the equations still hold. One of the nice things about linear algebra is that we can visually see what happens when the vectors are in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) or \(\mathbb{R}^3\), but higher dimensions are fine, too. The projection equations are used in least squares regression, where we want as many rows of data as possible to fit an equation to the data accurately.