2.5. Systems of Linear Equations¶

Systems of linear equations are everywhere in the systems that engineers design. Many (probably most) systems are linear. Differential equations sometimes describe systems, but we can change differential equations to linear equations by applying the Laplace transform. The main point, though, is that in actual design and analysis applications, we have systems of equations with multiple unknown variables, not just one equation.

The variables in linear equations are only multiplied by numbers. We do not have products of variables such as \(xy\) or \(x^2\). We also do not have exponentials such as \(e^x\) or functions of variables.

2.5.1. An Example¶

The following system of equations has three unknown variables.

The first step is to represent the equations as a matrix equation.

The common notation for describing this equation is \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{x} = \bm{b}\), where the vector \(\bm{x}\) represents the unknowns. In linear algebra notation, we describe the solution to the problem in terms of the inverse of the \(\bf{A}\) matrix, which is discussed in Calculating a Matrix Inverse, and

Elimination to Find the Matrix Inverse. Note that we have to be careful about the order of the terms because matrix multiplication is not commutative.

We can find the solution this way with the inv function, but Python

provides a more efficient way to solve it.

2.5.2. Jumping Ahead to Python¶

The solve function from either NumPy or SciPy finds the solution to a

square system of linear equations more efficiently than multiplying by the

inverse of a matrix. When we look at more advanced topics, then we will want

use other solver functions from SciPy and supply addition information to the

solvers.

In [1]: import numpy as np

In [2]: A = np.array([[2, -3, 0],[4, -5, 1],[2, -1,-3]])

In [3]: b = np.array([[3, 9, -1]]).T

In [4]: x = np.linalg.solve(A, b); x

Out[4]:

array([[3.],

[1.],

[2.]])

In [5]: from scipy import linalg

In [6]: x = linalg.solve(A, b); x

Out[6]:

array([[3.],

[1.],

[2.]])

Thus, the values of the three unknown variables are: \(x_1 = 3\), \(x_2 = 1\), and \(x_3 = 2\).

Note

Unlike MATLAB’s left-divide operator, the solvers in NumPy and SciPy do not examine the structure of the \(\bf{A}\) matrix to pick which algorithm to use.

We need to understand the available system solving algorithms and in what situations each is appropriate. Learning how to solve linear systems will also teach us about data analysis and other applications of linear algebra beyond systems of equations.

2.5.3. When Does a Solution Exist?¶

Not every matrix equation of the form \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{x} = \bm{b}\) has a unique solution. The possible solution scenarios to matrix equations with \(m\) rows and \(n\) columns (\(m{\times}n\)) of the form \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{x} = \bm{b}\) are described below.

There may be an exact, unique solution, which occurs with both critically-determined (square) and over-determined systems of equations. A few tests can help determine if a unique solution exists.

A solution may not exist, which can occur with any system of equations, but is usually associated with square, singular systems of equations.

The solution may be an approximated rather than an exact solution, which occurs with over-determined systems of equations.

The solution may be an infinite set of vectors, which occurs with under-determined systems of equations.

A square matrix system has a unique solution when the following five conditions hold for the matrix \(\bf{A}\). If one of the conditions holds, they all hold. If any condition is false, then all conditions are false and the matrix \(\bf{A}\) is singular and no solution to \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{x} = \bm{b}\) exists [WATKINS10].

\(\mathbf{A}^{-1}\) exists.

There is no nonzero \(\bm{x}\) such that \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{x} = \bm{0}\).

The \(\bf{A}\) matrix is full rank, \(\text{rank}(\mathbf{A}) = m = n\). The columns and rows of \(\bf{A}\) are linearly independent.

\(\det(\mathbf{A}) \neq 0\). The determinant is a well-known test for \(\bf{A}\) being invertible (not singular), but it is slow for larger matrices. The previous rank test is sufficient.

For any given vector \(\bm{b}\), there is exactly one vector \(\bm{x}\) such that \(\mathbf{A}\,\bm{x} = \bm{b}\).

The next example does not have a solution because the third row of

\(\bf{A}\) is a linear combination of rows 1 and 2

(4*A(2,:) + A(1,:)).

In [10]: A = np.array([[1, 2, 3],[0, 3, 1],[1, 14, 7]])

# A is not full rank

In [11]: np.linalg.matrix_rank(A)

Out[11]: np.int64(2)

# Not invertible

In [12]: np.linalg.det(A)

Out[12]: np.float64(0.0)

In [13]: b = np.array([[1, 2, 3]]).T

# This won't go well, so switch to minimal verbosity to show

# the exception message without the full traceback.

In [14]: %xmode Minimal

Exception reporting mode: Minimal

In [15]: linalg.solve(A, b)

LinAlgError: Matrix is singular.

The next example has a better result.

In [18]: A = np.array([[5, 6, -1],[6, 3, 2],[-2, -3, 6]])

In [19]: np.linalg.matrix_rank(A) # full rank

Out[19]: np.int64(3)

In [20]: b = np.array([[8, 0, 8]]).T

In [21]: x = linalg.solve(A, b); x

Out[21]:

array([[-2.88888889],

[ 4.14814815],

[ 2.44444444]])

2.5.4. Column and Row Factorization¶

A matrix factoring converts a matrix into two or more sub-matrices whose product yields the original matrix. Matrix factorization, or decomposition, is quite common in linear algebra and is used when the submatrices are needed for implementing algorithms. Here, we present a factorization that is not used in any algorithms. Its purpose is solely to provide information and, more importantly, to facilitate learning about systems of equations. The CR (for column–row) factoring of matrix \(\bf{A}\) produces matrix \(\bf{C}\) that consists of the independent columns of \(\bf{A}\) and another matrix, \(\bf{R}\), showing how combinations of the columns of \(\bf{C}\) are used in \(\bf{A}\) [MOLER20]. The CR factoring was proposed by Dr. Gilbert Strang [1] of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology [STRANG20]. The CR factorization aims to illustrate concepts related to independent and dependent columns and how dependent columns degrade systems of equations.

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

# File: cr.py

#

import numpy as np

from sympy import Matrix

def cr(A: np.array) -> tuple[np.array, np.array]:

# C,R = cr(A) is Strang's column-row factorization, A = C @ R.

# If A is m-by-n with rank r, then C is m-by-r and R is r-by-n.

M = Matrix(A)

Rm,j = M.rref()

r = len(j)

R = np.array(Rm[:r,:], dtype=float)

C = A[:,j]

return C,R

if __name__ == "__main__":

A = np.random.randint(-5, 10, (3,3))

A = A.astype(float)

C, R = cr(A)

# print(A == C @ R)

print("Random Matrix:")

print(f'C = \n{C}\n')

print(f'R = \n{R}\n')

print("Singular Matrix:")

A[:,2] = A[:,0] + A[:,1]/2

C, R = cr(A)

print(f'C = \n{C}\n')

print(f'R = \n{R}\n')

The cr function uses the rref function to perform Gaussian

elimination as described in Reduced Row Echelon Form. For now, consider the output

of cr rather than its implementation.

When we use the test code in cr.py, we first use the CR factorization

with a random \(3{\times}3\) matrix, which will almost always have

independent columns. In the

CR factoring, the \(\bf{C}\) matrix is the same as \(\bf{A}\).

The \(\bf{R}\) matrix is an identity matrix, indicating that each

column of \(\bf{C}\) is found unchanged in \(\bf{A}\). Matrices

with independent rows and columns are said to be full rank.

Then the test code changes the \(\bf{A}\) matrix, making the third column a linear combination of the first two. The rank of the matrix is then 2. We can see the rank from the CR factorization as the number of columns in \(\bf{C}\) and the number of rows in \(\bf{R}\). The last column of \(\bf{R}\) shows how the first two columns of \(\bf{C}\) combine to make the third column of \(\bf{A}\).

Random Matrix:

C =

[[ 2. 8. 6.]

[ 5. -4. 2.]

[-5. 8. -2.]]

R =

[[1. 0. 0.]

[0. 1. 0.]

[0. 0. 1.]]

Singular Matrix:

C =

[[ 2. 8.]

[ 5. -4.]

[-5. 8.]]

R =

[[1. 0. 1. ]

[0. 1. 0.5]]

- Rank

The rank, \(r\), of a matrix is the number of independent rows and columns of the matrix. Rank is never more than the smaller dimension of the matrix.

The CR factoring helps us to see if some rows or columns are linear combinations of other rows or columns. The

crfunction shows one way to compute a matrix’s rank: the number of nonzero pivot variables from the elimination algorithm, which are the diagonal elements of \(\bf{R}\). See Vector Spaces and Rank from the SVD for more information on calculating a matrix’s rank.

2.5.5. The Row and Column View¶

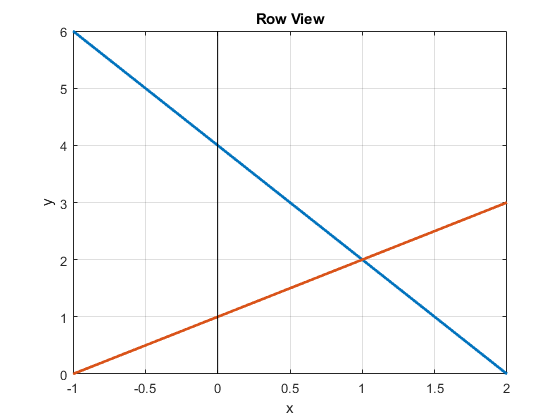

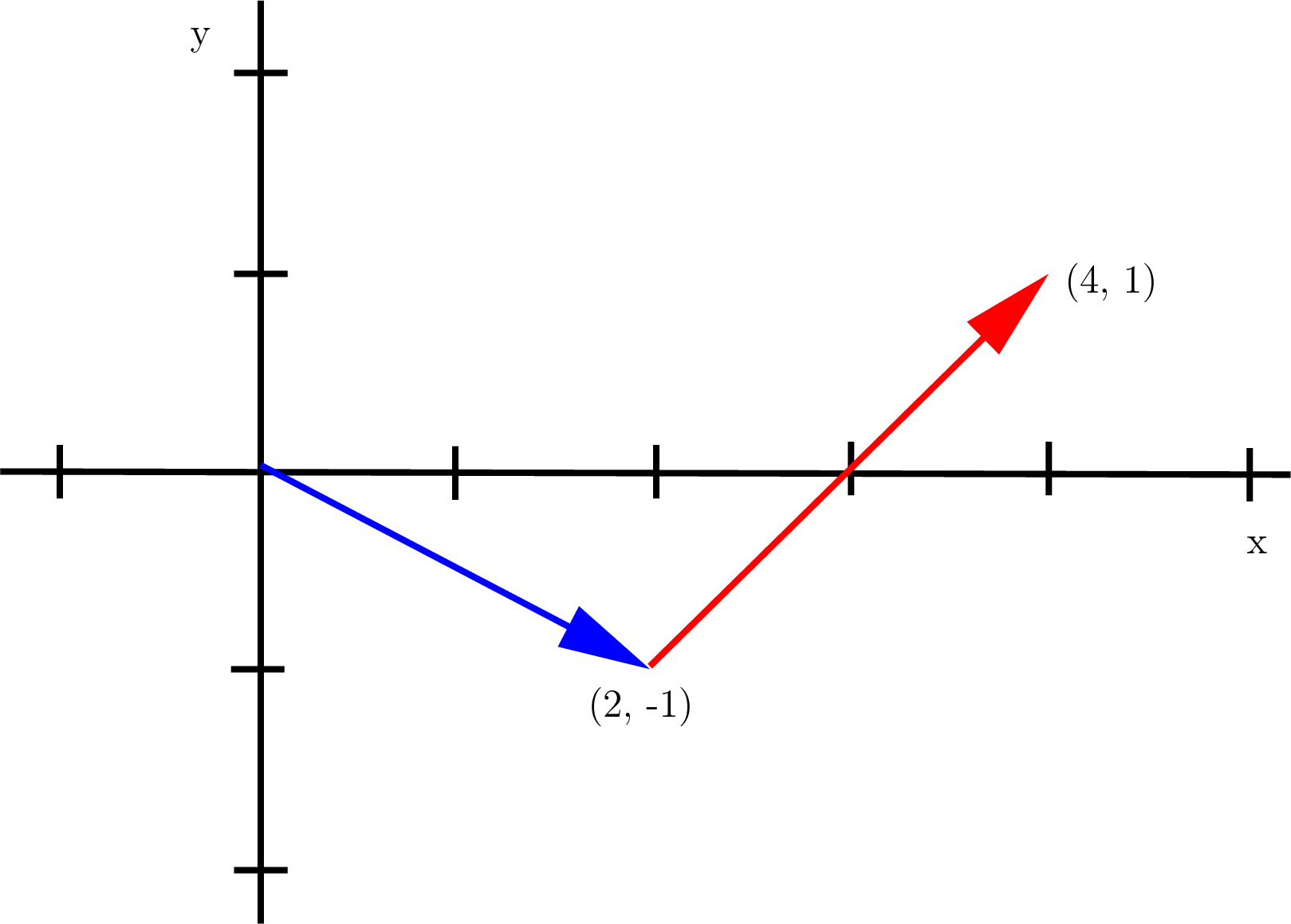

A system of linear equations may be viewed from the perspective of either its rows or its columns. Plots of row line equations and column vectors give us a geometric understanding of systems of linear equations. The row view shows each row as a line, with the solution being the point where the lines intersect. The column view shows each column as a vector and presents the solution as a linear combination of the column vectors. The column view yields a perspective that will be particularly useful when we consider over-determined systems.

Let’s illustrate the two views with a simple example.

To find the solution, we can either use the solve function or elimination, which is discussed in Elimination.

Row View Plot

We rearrange our equations into line equations.

As shown in figure Fig. 2.18, the point where the lines intersect is the solution to the system of equations. Two parallel lines represent a singular system that does not have a solution.

Fig. 2.18 In the row view of a system of equations, the solution is where the line equations intersect.¶

If another row (equation) is added to the system, making it over-determined, an exact solution can still be found if the new row is consistent with the existing rows. For example, we could add the equation \(3x + 2y = 7\) to the system, and the line plot for the new equation will intersect the other lines at the same point, so \(x = 1; y = 2\) is still valid. We could still say that \(\bm{b}\) is in the column space of \(\bf{A}\). Of course, most rows that might be added will not be consistent with the existing rows, so we can only approximate a solution, which we will cover in Perspective Projection Model.

Column View Plot

Let’s view the system of equations as a linear combination of column vectors.

Fig. 2.19 The column view shows a linear combination of the column vectors. Each vector is scaled such that the sum of the vectors is the same as the vector on the right side of the equation.¶

As depicted in figure Fig. 2.19, there is a nonzero linear combination of the column vectors of a full rank matrix that can reach any point in the vector space except the origin. When \(\bf{A}\) is full rank and vector \(\bm{b}\) is nonzero, then \(\bm{b}\) is always in the column space of \(\bf{A}\). The all-zero multipliers provide the only way back to the origin for a full rank system. But a singular system with parallel vectors can have a nonzero vector leading back to the origin, which is called the null solution (Null Space).

Footnote